Starting next year, thousands of our neighbors in Allegheny County – where 1 in 7 face food insecurity – will lose their food stamp benefits.

Starting next year, thousands of our neighbors in Allegheny County – where 1 in 7 face food insecurity – will lose their food stamp benefits.

Since the reform of welfare in 1996, federal law has required that able-bodied adults without dependents – “ABAWDs” as they are referred to in public policy – work or participate in a work program for at least 20 hours a week. Otherwise, they can only receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or “food stamps”) benefits for three months out of a three-year period. This policy applies to people ages 18-49 who are lacking a physical or mental disability. (Read more about SNAP work requirements here.)

People in the ABAWD category are some of the poorest people in the country. USDA data show these individuals have average incomes of 19 percent of the poverty line (or $2,200 annually) and they generally do not qualify for any other type of income support.

But states can waive the three months in three years time limit if unemployment rates are high. In 2004, PA was granted a waiver due to the rise in our unemployment rates and in 2009, nearly all states were granted waivers because of the Great Recession. But now that the economy is supposedly doing better (though the nation’s economic “recovery” has left millions of Pennsylvanians behind), most states’ waivers are expiring in January, and Pennsylvania’s is ending this March. If able-bodied but unemployed individuals don’t meet the work requirements, their benefits will end by June.

The requirement is meant to be a work incentive, as if able-bodied individuals who receive food stamps aren’t working simply because they’re lazy.

In fact, there is not enough work for those who need it. Even though the unemployment rate is slowly falling, the economic recovery has not reached all Americans. Often, workers seeking full-time work can only find part-time employment.

The unemployment rate doesn’t include those discouraged workers who have searched for jobs without any luck for so long they’ve given up looking. Further, compared to other states, Pennsylvania ranks low for job growth: 40th in the nation.

Even without these factors, able-bodied adults can have trouble finding work even in normal economic times, as many face a variety of barriers to work, such as inadequate access to transportation, criminal histories, limited education, language limitations, or homelessness. The ABAWD population includes many youths leaving foster care, ex-offenders wanting to reintegrate into society, and veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Taking away food assistance – causing people hunger – is not a way to motivate people to find work because they’re likely already hungry. The maximum food stamp benefit is only $194 a month (around $2/meal) for a single able-bodied adult. Food stamps are only meant to supplement the recipient’s food budget.

When people face food insecurity, they react by adjusting their budgets, reducing how much they eat, and reducing the variety of foods they eat. So, they spend less on food, eat less, and instead of consuming a varied diet with lots of fruits and vegetables, they tend to rely on cheaper, energy-rich foods like refined grains, added sugars, and added saturated and trans fats. A diet such as this is linked to chronic diseases, such as obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia (high cholesterol), and diabetes – diseases that carry their own costs and that leave those afflicted less able to be employed.

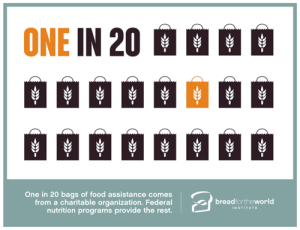

Cutting food stamps doesn’t mean that people find the money to buy food elsewhere—instead, it places undue stress on food charities. And all 8,000 ABAWDs can’t all rely on organizations such as the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank or other community pantries, which already work hard to provide food to our area’s hungry people.

Cutting food stamps doesn’t mean that people find the money to buy food elsewhere—instead, it places undue stress on food charities. And all 8,000 ABAWDs can’t all rely on organizations such as the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank or other community pantries, which already work hard to provide food to our area’s hungry people.

And keep in mind that as Center for American Progress research demonstrates, deepening hunger in America has its own costs. As of their tally in 2011, these costs had topped $6 billion in PA.

Able-bodied unemployed individuals don’t need sanctions. They need the resources that will help them find work – like job training, job search help, and transitional education. But unfortunately, federal law does not require that states offer a job training spot to every able-bodied childless adult who wants one, and Pennsylvania does not have enough slots to serve all 8,000 people in that category.

What You Can Do

Luckily, ABAWD individuals can do 26 hours of community service a month to continue receiving benefits, which is why Just Harvest is forming a coalition of non-profit partners that will commit to offering volunteer spots to those who can’t meet work requirements and need to keep their food stamps.

Are you an organization that can offer volunteer spots to ABAWDs, or do you know of an organization that we should contact? Let us know by contacting me at kalenat@justharvest.org.

No comments yet.